Decoding Egyptian Hieroglyphs: the Rosetta Stone, Champollion, and Young

It had been over a thousand years since anyone had written or understood Egyptian hieroglyphs. Many had tried to decipher this hieroglyphic script and failed.

So, how did Jean-Francois Champollion succeed where others had failed for centuries before him? What were the keys to his success?

Early Advances in Decipherment

The year is 1822, and scholars have been making some headway into understanding two types of scripts that the ancient Egyptians used, the more famous hieroglyphic script and the demotic script, which was used from the Late Period to the end of Pharaonic history as a kind of cursive script.

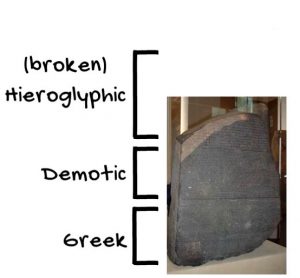

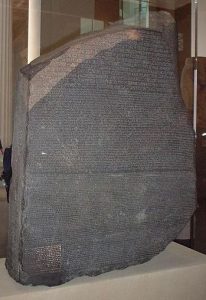

The recent breakthroughs have been largely due to the French army’s 1799 discovery of a peculiar stone in a military fort wall at the town of Rashid (often called by its Greek name, Rosetta).

This curious stone, which would come to be called the Rosetta Stone, had been reused to build that wall, as it was clearly ancient and had three inscriptions on it, one in Greek, one in demotic Egyptian, and one in hieroglyphic Egyptian.

Rather watch than read? Check out our YouTube video.

Using the texts on the Rosetta Stone, which are identical in content, though written in two different languages and three different scripts, scholars such as J. H. Åkerblad and A.I. Sylvestre de Sacy made significant contributions to understanding Egyptian writing, especially the demotic script.

For this script, they had figured out things like the names of kings and queens, some pronouns, and a few other words in the demotic portion of the stone.

Thomas Young

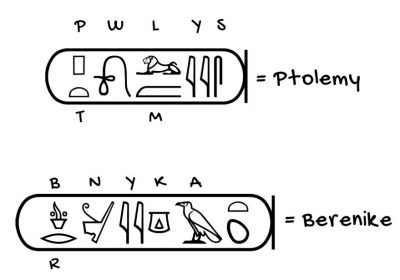

With this groundwork lain, the English polymath Thomas Young was able to compare the hieroglyphic signs within ovals – or cartouches – to the royal names, such as Ptolemy and Berenike, that appeared in the Greek text.

By doing this, Young was able to figure out the phonetic sounds of the Egyptian signs, such as a box for the sound of the letter “p”, a loaf of bread for the sound of the letter “t”, and a folded cloth for the sound of the sound “os” (now understood as just “s”).

Before this time, it was universally believed that hieroglyphs were purely symbolic in meaning. That is, each sign or set of signs conveyed ideas, concepts, or things, but not sounds such as an alphabet or a syllabic script would do.

This new work showed that there were some signs that could be used to represent sounds, at least for when transcribing foreign names, such as the Greek name Ptolemaios (Ptolemy).

The other Egyptian script on the Rosetta Stone, demotic, was assumed to be alphabetic, unlike Egyptian hieroglyphs. However, Young figured out that the demotic script actually had developed from hieroglyphs and, thus, could not be a pure alphabet.

He recognized the similarity that some of the demotic signs had with the corresponding hieroglyphic text. This caused a problem, since it was believed that demotic was a purely phonetic (sounds-based) alphabet, while hieroglyphs were symbolic and carried no sound value, with the exception of those used to write foreign names.

Want to learn Egyptian hieroglyphs? Download my free guide to get started:

Young determined that, in fact, demotic was composed of both symbolic or conceptual signs and alphabetic signs. However, Young was unable to take the next step and apply this same idea to the hieroglyphs.

Although he could not figure out how the hieroglyphic signs he saw on the Rosetta Stone could work conceptually to convey the same things that the Greek version of the inscription said, he still believed, as did everyone else at the time, that the Egyptian hieroglyphs had purely conceptual or symbolic meaning, rather than representing sounds.

Jean-Francois Champollion

Photo credit: Elliot Brown

Enter the Frenchman Jean-Francois Champollion, a man who had obsessively studied a wide variety of written languages since he was a boy and had become an expert in Coptic, the language used in the Egyptian Christian Church.

Initially, Champollion was no different than those who came before him and believed Egyptian hieroglyphs to be purely symbolic in meaning. However, by 1822, Champollion had changed his mind, but only in relation to foreign names, like Thomas Young.

Once he had made that shift in his ideas about Egyptian hieroglyphs, he was able to figure out many additional phonetic hieroglyphs beyond what Young had done by examining the names of Greek and Roman rulers in Egyptian texts.

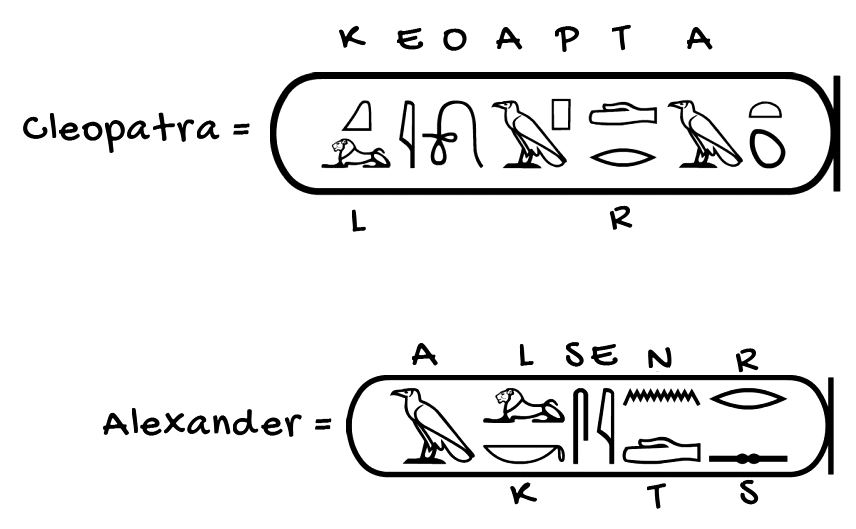

Luckily, by 1822 he now had access to copies of many more inscriptions than were previously available to researchers. In these inscriptions – most notably on the so-called Bankes Obelisk – he had access to a variety of new Greek and Roman names. The Bankes Obelisk had a text in Greek on its base that he could use to compare to the names of Ptolemy and Cleopatra in the hieroglyphs.

Champollion had also gained access to a papyrus with texts in Greek and demotic, which allowed him to figure out the demotic spelling of the name Cleopatra. This breakthrough in demotic allowed Champollion to hypothesize how Cleopatra would be spelled in hieroglyphs because he had already recognized the equivalencies between many demotic and hieroglyphic signs. Between this and the hieroglyphs that he already knew from the name of Ptolemy on the Rosetta Stone – those for “L,” “E,” “O,” and “P” – he was able to identify the name of Cleopatra on the Bankes Obelisk.

To test whether he was correct in interpreting the second name on the Bankes Obelisk as that of a queen named Cleopatra, Champollion started applying his interpretation of these hieroglyphs to other names that he found in cartouches from other monuments. For example, this one A L ? S E ? T R ? – Champollion guessed that this entire name included the sounds A L K S E N T R S, which would equate to the Greek name Alexandros (Alexander). Champollion continued on in this manner for all of the foreign names that he could find.

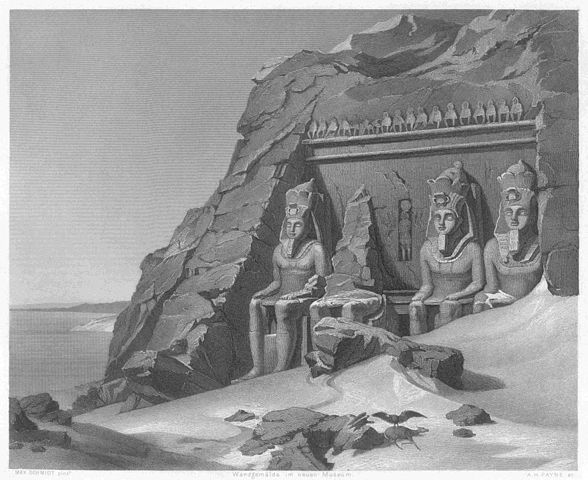

Around this same time, he received a copy of an inscription from the temple of Abu Simbel. In this inscription was a royal name that he had not deciphered yet, an Egyptian name.

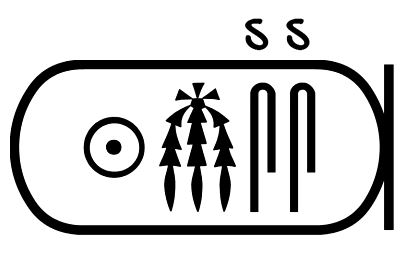

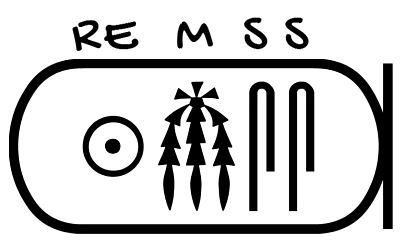

The name was written several different ways, but the simplest form of the name had four signs, and, as luck would have it, Champollion was already familiar with two of them from his work on Greek and Roman names: ss.

The first sign in the cartouche looked like a sun, so Champollion guessed that it might have the same phonetic meaning as the Coptic word for sun: re.

Once he had Re _ ss, Champollion thought about the names of Egyptian Pharaohs known from the history of Egypt written in Greek by an Egyptian priest named Manetho during the 3rd century B.C. and he realized that this name bore a striking resemblance to the name Ramesses! Based on this idea, he thought that the middle sign must represent the letter “M.”

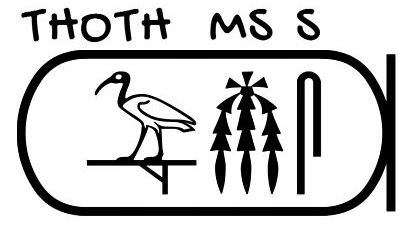

He then moved on to another name in a cartouche: the first sign, a picture of an Ibis, was known to be a symbol of the god Thoth. Champollion put this together with the other signs that he now knew and figured out that this name must be Thutmosis (Thothmes), a Pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty who was named in Manetho’s history.

Champollion then realized that the sign he believed to be “M” was used on the Rosetta Stone in the places where the Greek text talked about birthdays, suggesting that this sign also spelled out the word for “birth,” which in Coptic was “mise” (since the hieroglyphs represent only consonants and not vowels, the sign actually stands for the two consonants “M” and “S”). Now Champollion had finally found the key! He was able to keep going to the next name and the next name.

When he made this breakthrough, Champollion reportedly ran to his older brother’s office, burst in and said, “I’ve done it!” He then passed out before he could explain to his brother what he had figured out.

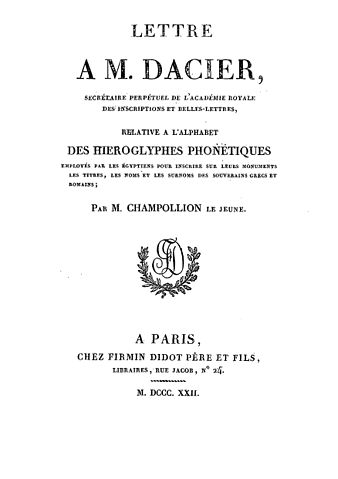

He was unconscious for five days, after which he returned to work and, only about a week later, he gave a lecture on the topic at the Academy of Inscriptions and Belles-Lettres announcing his breakthrough. He would publish this lecture the following month as the now famous Lettre à M. Dacier.

However, up to this point, Champollion still believed that – other than when used for names – hieroglyphs typically represented ideas or things, not sounds.

It was not long after this, though, when, in the following year, Champollion was finally able to take the next step and create his system, or “key,” to move on from names to other words in Egyptian.

How did he do this? He never explained his exact process, but we can put together a few events from the time to help explain his breakthrough.

Champollion realized that there were not nearly enough hieroglyphic signs on the Rosetta Stone to be able say everything that the Greek version of the text said if the hieroglyphs each represented a single thing or idea.

Perhaps also influenced by a recently published grammar of Chinese, which showed that many of the signs in Chinese were phonetic – that is, they represented sounds – rather than representing things or ideas, Champollion finally realized that many Egyptian hieroglyphs were also purely phonetic.

Once he had this piece of the puzzle, he was able to use his intimate knowledge of Coptic and its vocabulary with his new found ability to recognize the sounds of many hieroglyphic signs in order to start deciphering hieroglyph after hieroglyph and word after word. He would subsequently publish a more comprehensive study of the hieroglyphic system of writing in 1824.

Whose Discovery?

Ever since Champollion published his findings, which he did largely without acknowledging Young’s important work, there has been a fierce debate about whether he used Young’s ideas without crediting him or whether Young’s discoveries had no influence on Champollion, who instead had reached the same conclusions on his own.

Opinions often fall along nationalistic lines, with those from England tending to see Champollion’s work as based on that of Young without due acknowledgement and those from France tending to see Young as unimportant in the path to decipherment and Champollion has having been the only serious innovator.

While the debate about who should receive how much credit will likely continue, the British Egyptologist Richard Parkinson perhaps sums it up best by writing:

“Even if one allows that Champollion was more familiar with Young’s initial work than he subsequently claimed, he is the sole decipherer of the hieroglyphic script: as Peter Daniels sates, any ‘decipherment stands or falls as a whole.’ Young discovered parts of an alphabet – a key – but Champollion unlocked an entire language.”

To learn more about the decipherment of ancient Egyptian writing, check out the recommended books below.

If you’re interested seeing more on this site about ancient Egyptian writing and its decipherment in the future, let me know in the comments what topics or questions you would like me to address in future posts.

Want to learn Egyptian hieroglyphs? Download my free guide to get started:

☥☥ HELPFUL BOOKS☥☥

(Note: the following links are affiliate links, which means that I receive a small commission when you make a purchase. I only recommend books that I personally have read and know are of a high quality. This helps support the blog and channel and allows me to continue to make videos and posts like this one. Thank you for your support!)

☥ Andrew Robinson, Cracking the Egyptian Code

An engaging read about Champollion, his brother, and other scholars who were trying to decipher ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs in the nineteenth century (and before).

Robinson provides both a biography of Champollion and a detailed play-by-play of the decipherment itself, including who all the players were in the decipherment game.

☥ Richard Parkinson, Cracking Codes: The Rosetta Stone and Decipherment

A wonderful overview of the Rosetta Stone, decipherment of hieroglyphs, and an introduction to how hieroglyphs (and other ancient Egyptian scripts) actually work.

This is a catalog that accompanied a museum exhibit, so it also includes many black and white and some color photographs of ancient Egyptian objects and the people involved in decipherment.

☥☥QUOTED TEXTS☥☥

☥ Richard Parkinson quote:

Richard Parkinson, Cracking Codes: The Rosetta Stone and Deciperment. Berkeley; Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1999, pp. 40. http://amzn.to/2gGKS9S